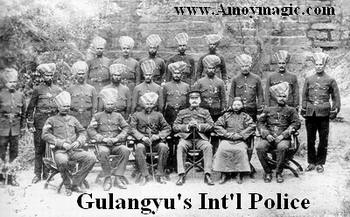

International Settlements, such as that on our own Gulangyu Islet a century ago, were indeed

self-governed foreign enclaves, where both foreigners and rich Chinese could live above the Chinese law. But the idea for these settlements initially came from the Chinese, not the foreigners--though foreigners carried it much further than Chinese intended, basically setting themselves above the law anywhere in China. Even when our family arrived in Xiamen in 1988, foreigners were not allowed to live with Chinese. We were housed in the "Holiday Village", which was chained and padlocked every night from 11 PM to 7 AM--from the outside (for our safety, we were told). I asked what happened in case of fire and was told that they'd unlock it. We'd have never imagined back then how completely Xiamen would change, and open up, over the next 20 years.

self-governed foreign enclaves, where both foreigners and rich Chinese could live above the Chinese law. But the idea for these settlements initially came from the Chinese, not the foreigners--though foreigners carried it much further than Chinese intended, basically setting themselves above the law anywhere in China. Even when our family arrived in Xiamen in 1988, foreigners were not allowed to live with Chinese. We were housed in the "Holiday Village", which was chained and padlocked every night from 11 PM to 7 AM--from the outside (for our safety, we were told). I asked what happened in case of fire and was told that they'd unlock it. We'd have never imagined back then how completely Xiamen would change, and open up, over the next 20 years.As far as we know, our family was the first in Xiamen to be allowed to live in "Chinese" housing, but today it is the norm. Foreign teachers at Xiamen University are given a housing allowance and allowed to rent any place they desire. Some foreigners even purchase apartments or villas. The only requirement is that they register their address with the local police (the same requirement made of Chinese).

What a change from 20 years ago--or 80 years ago, when Ann Mackenzie-Grieves wrote about international settlements in her book "A Race of Green Ginger" (she lived on Gulangyu in the 1920s):

To hear the students one would have thought that the foreign settlements had been a wicked invention of the Western traders and imperialists. Actually, since the Portuguese began trading with the southern Chinese in the sixteenth century, Chinese relationship with the foreigners had been entirely governed by China's own system of administrative responsibility. The foreigners proved far easier to control in a settlement of their own, under their own headman, who, like a Chinese civil governor, could be held entirely responsible for their behaviour. During the next two centuries the arrangement worked well. There were times when both Chinese and Westerners behaved badly: unlettered Manchu successors of the Ming scholar-officials were arbitrary and obstinate; hectoring British traders abused privileges, flouted the custom and courtesy so vital to Chinese relationships; tough sea-captains resorted to violence. On the whole, however, it was to the advantage of both sides to abide by the rules. But the immunity of extra-territoriality accorded to the foreigners in their own enclaves began to be extended to, and claimed by, Chinese living in the concessions and, with the increasing corruption and misgovernment of nineteenth-century China, Chinese ships found it safer to sail under foreign flags. Smugglers, both foreign and local, sailed profitably under any flag they could buy, and strengthened their alliance with the pirates….

Mackenzie-Grieves, 1959, pp. 101,102.

www.amoymagic.com

No comments:

Post a Comment